Discovery of the ‘Sandycove Atlas’

Joyce is famous for having been, as his biographer Richard Ellmann put it, ‘tenacious of remembered facts’.1 Ulysses in particular refracts a myriad of real events through the unsettling lenses of Joyce’s vision. Even now, more than 100 years after its publication in 1922, we are still uncovering more of the real people, places, things and events behind his portrayal of Dublin life. I believe the Sandycove Atlas could be just such a discovery, made by pure chance.

The discovery hinged on the second episode of Ulysses’, ‘Nestor’, which closely reflects Joyce’s brief career as a schoolmaster at Clifton School, in Dalkey, a seaside suburb of Dublin. Joyce is believed to have taught there for a short time in the summer term of 1904. The headmaster was Francis Irwin, remodelled for Joyce’s purposes as ‘Mr Deasy’, the Nestor figure who advises young Stephen Dedalus in sententious fashion.

Deasy is generally seen as a composite of Irwin himself and Henry Blackwood Price, an Ulsterman Joyce knew in Trieste. Joyce presents Irwin’s imperialism through the pictures and ornaments in Deasy’s study as well as his chauvinist views, while a passage where Deasy laboriously types a letter on foot-and-mouth disease for Dedalus to place in The Evening Telegraph reflects an obsession of Blackwood Price’s.

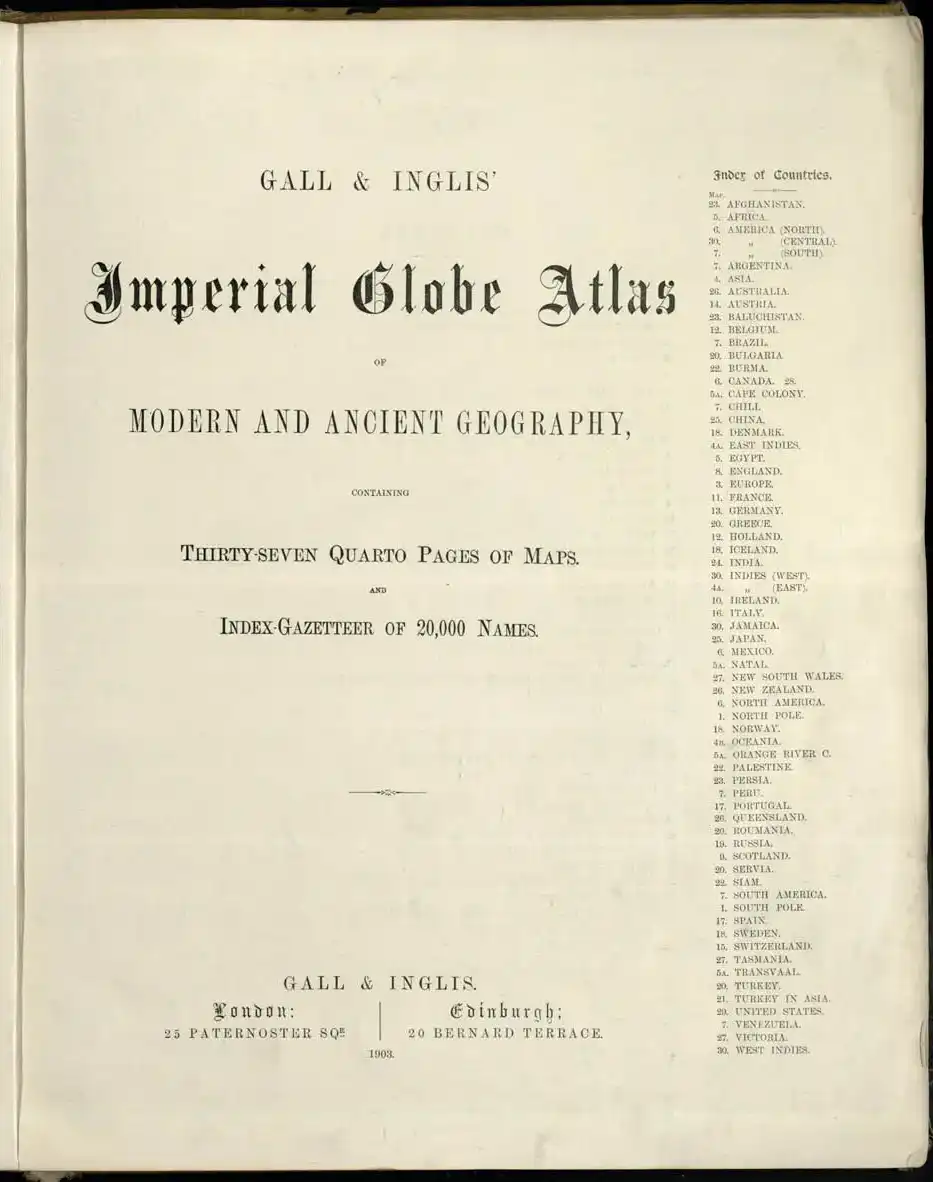

The Title Page corresponds to the identification document for a publication

King Pyrrhus (319-272 BCE) was a famously successful general. He was invited by the citizens of Tarentum to save them from being absorbed into the Roman Empire.

Despite King Pyrrhus’ efforts, Tarentum was eventually defeated. These Roman columns still stand there.

In the scene opening ‘Nestor’, Stephen Dedalus takes his pupils through a lesson on the Pyrrhic Wars, fought in southern Italy about 280BC. He begins by asking for some key facts about the Wars which he has evidently set as homework:

- ‘You, Cochrane, what city sent for him?

- Tarentum, sir.

- Very good. Well?

- There was a battle, sir.

- Very good. Where?

The boy’s blank face asked the blank window.

Fabled by the daughters of memory. And yet it was in some way if not as memory fabled it. A phrase, then of impatience, thud of Blake’s wings of excess. I hear the ruin of all space, shattered glass and toppling masonry and time one livid final flame. What’s left us then?

- I forget the place sir.

Asculum, Stephen said, glancing at the name and date in the gorescarred book.

Yes sir. And he said: Another victory like that and we are done for.’

The Pyrrhic Wars of 280-275BC started when the citizens of Tarentum called on King Pyrrhus of Epirus to help them in their struggle against Rome. The war is still memorable for giving us the phrase ‘Pyrrhic Victory’, meaning a battle won at ruinous cost.

But did this lesson really happen? Or did Joyce just invent it as a vehicle for his points about the futility of war?

In 2019, during a short holiday with my wife in Ireland, I was so fortunate as to discover a document which I believe provides strong evidence that the lesson on the Pyrrhic Wars was absolutely authenitic. What is more, this same document seems to foreshadow many other ideas and incidents in Joyce’s work. It could provide a key to some mysterious references and improve our understanding of the relationship between Joyce and his muse, Nora Barnacle, in the months of their first meeting and their courtship.

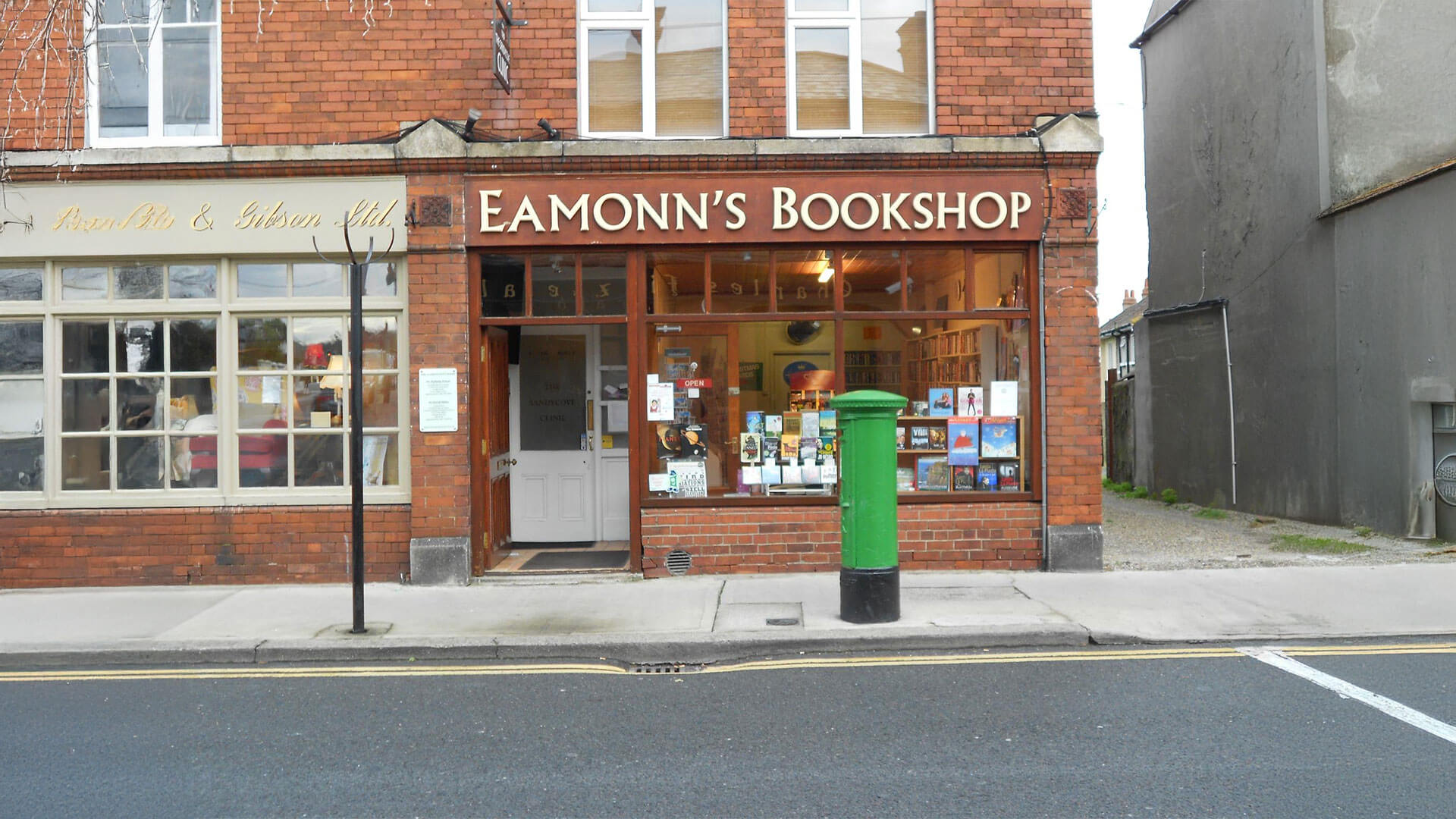

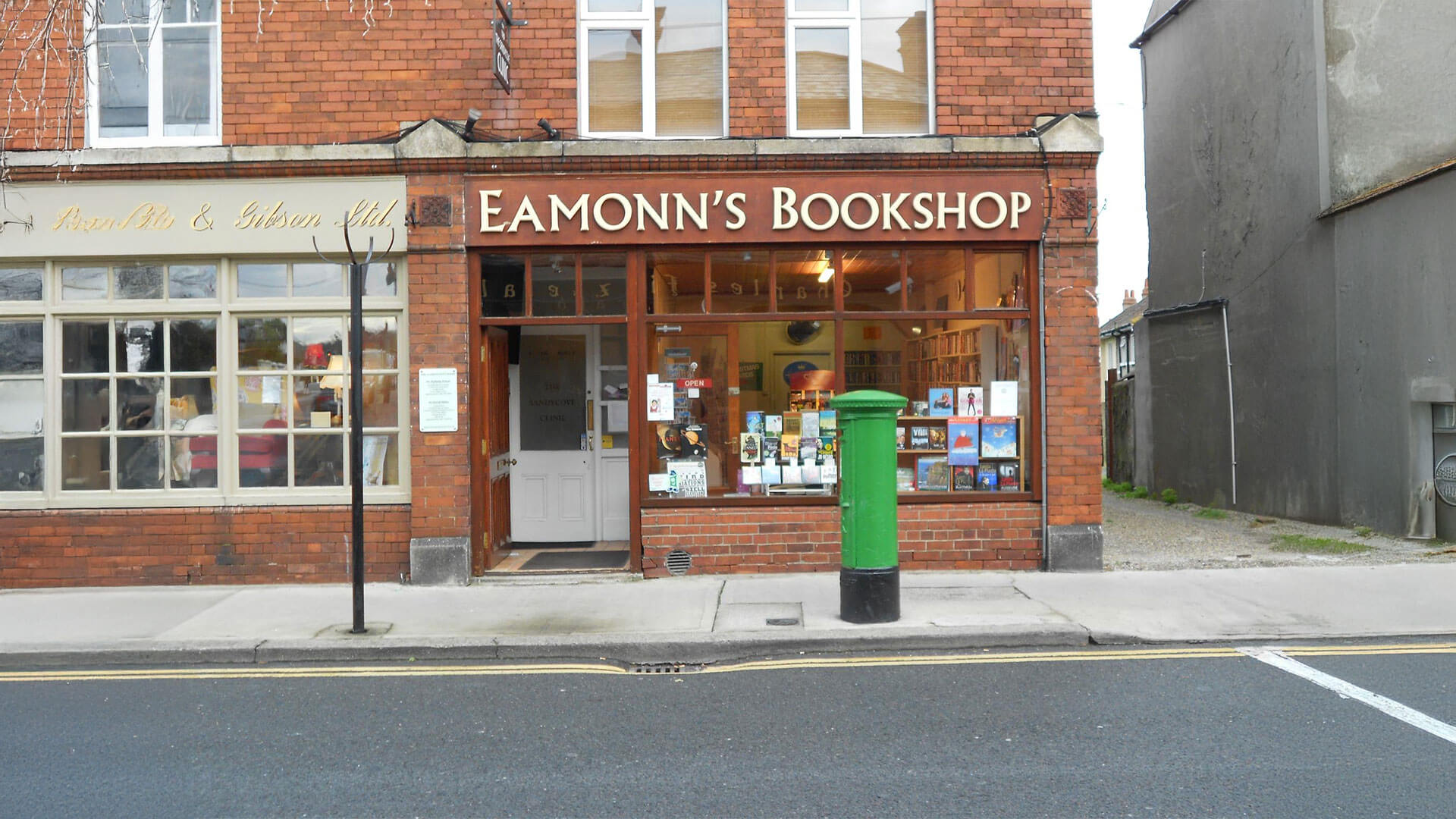

Eamonn Buckley has been trawling the Dun Laoghaire area for books to sell since the 1970s.

Bought for 5 euros

I had Ulysses with me on the holiday and was keen to visit what is now known as Joyce’s Tower, one of the Martello Towers built along the shorelines of England and Ireland as a defence against invasion during the Napoleonic Wars. Famously, Joyce spent about a week living in the Tower in September 1904 and immortalised it as the setting for the first episode of Ulysses. Now it is an international tourist attraction in the seaside suburb of Sandycove, about a mile closer to Dublin than where Joyce taught school. Visitors can climb the steps from which ‘Stately, plump Buck Mulligan’ emerged onto the roof and see the same views. Inside there is furniture and other household goods which, even if they are not the ones which Joyce used when he was there, look just the same.

My wife and I talked to two of the volunteers staffing the museum. They encouraged me on my voyage with Ulysses and recommended a nearby pub, Fitzgerald’s of Sandycove. There we studied the series of stained-glass windows illustrating each episode of the novel and enjoyed a good lunch.

Right opposite the pub I noticed Eamonn’s Bookshop and took a spare moment to go inside in search of maps or atlases. At first sight it didn’t look very promising. Eamonn’s Bookshop specialises in near-new books plus CDs and DVDs. And when I asked the bookseller – Eamonn himself – if they had any maps or atlases, he said no, but then remembered a battered volume, up on a high shelf.

Only as I examined this ‘Sandycove Atlas’ on the train did I start to think that it might be even more interesting than I thought. I had already noticed marks by an earlier reader on many of the plates. This was no drawback to me. I’ve been scribbling on maps since I was a small child (with indulgent parents) and I like maps which reveal something of how they have been used.

The Imperial Globe Atlas earns its title to covering ancient geography by including two historical plates right at the end; ‘The world as known to the ancients’ and ‘Italia & Graecia’. The ancient world map has no marks but coming to the very last plate in the Atlas I noticed a cluster of underlinings, in pencil, of city names in the very south of Italy. My mind clicked over to Stephen Dedalus’ history lesson. Could these be some of the towns he was asking his pupils to identify?

When we got back to our top-floor hotel room overlooking St Stephens Green in Dublin, the first thing I did was to look in Ulysses. Yes! There was Tarentum, quoted in line 2 of Nestor, and there was Asculum too!

More scrutiny of the Atlas revealed ten pencil underlines in southern Italy, and later research showed that most of them were clearly related to the Pyrrhic Wars. Tarentum was the city which asked Pyrrhus, King of Epirus for help in their struggle against the Romans, Asculum was where he defeated them in 279BC, Parthenope was one of the cities which Pyrrhus wasted, Beneventum was where the Romans eventually defeated Pyrrhus, in 275BC – and so on.

These places were not underlined at random. The only way someone would have selected these 10 obscure towns was if they were teaching, or in some way studying, the Pyrrhic Wars. As such, the marks on the Atlas bear witness to the realism of the scene at the beginning of ‘Nestor’ and, once again, to the authenticity of Joyce’s own ‘map’ of Dublin in June 1904.

Joyce photographed by his friend C P Curran in 1904

Return to Ireland

In July 2023 I returned to Ireland to make a short video about the Atlas, its discovery, and what Joycean experts think of it. The video was made by Ciaran O’Connor and his team at New Decade productions1 .

It is fair to say that none of the three interviewees believed in my claims for the Atlas. But Ciaran’s incisive interviewing style led to a key revelation. Between them, the interviewees vouch for the situation (school use), the place (within a few miles of Sandycove) and the motivation (promoting imperialism) which all fit closely with the Nestor, the second episode of Ulysses.

The video alone is far from proving that James Joyce used the Atlas, but it shows that it is entirely possible he could have done.

Possibilities

Since that amazing day in July 2019 I have had some of the most interesting days of my life, finding further links between the Atlas and Ulysses, and even to Joyce’s other works. Lockdown, illness and simple aging have combined to slow my progress in presenting them to the world. I have not yet been able to engage Joyceans – or anyone else who enjoys a literary conundrum – with what the Atlas may have to contribute.

Now I hope the launch of this website will enable many people to study the extraordinary user marks in the Atlas and what they could imply for our understanding of Joyce’s great legacy.

Tim Johnson, April 2025

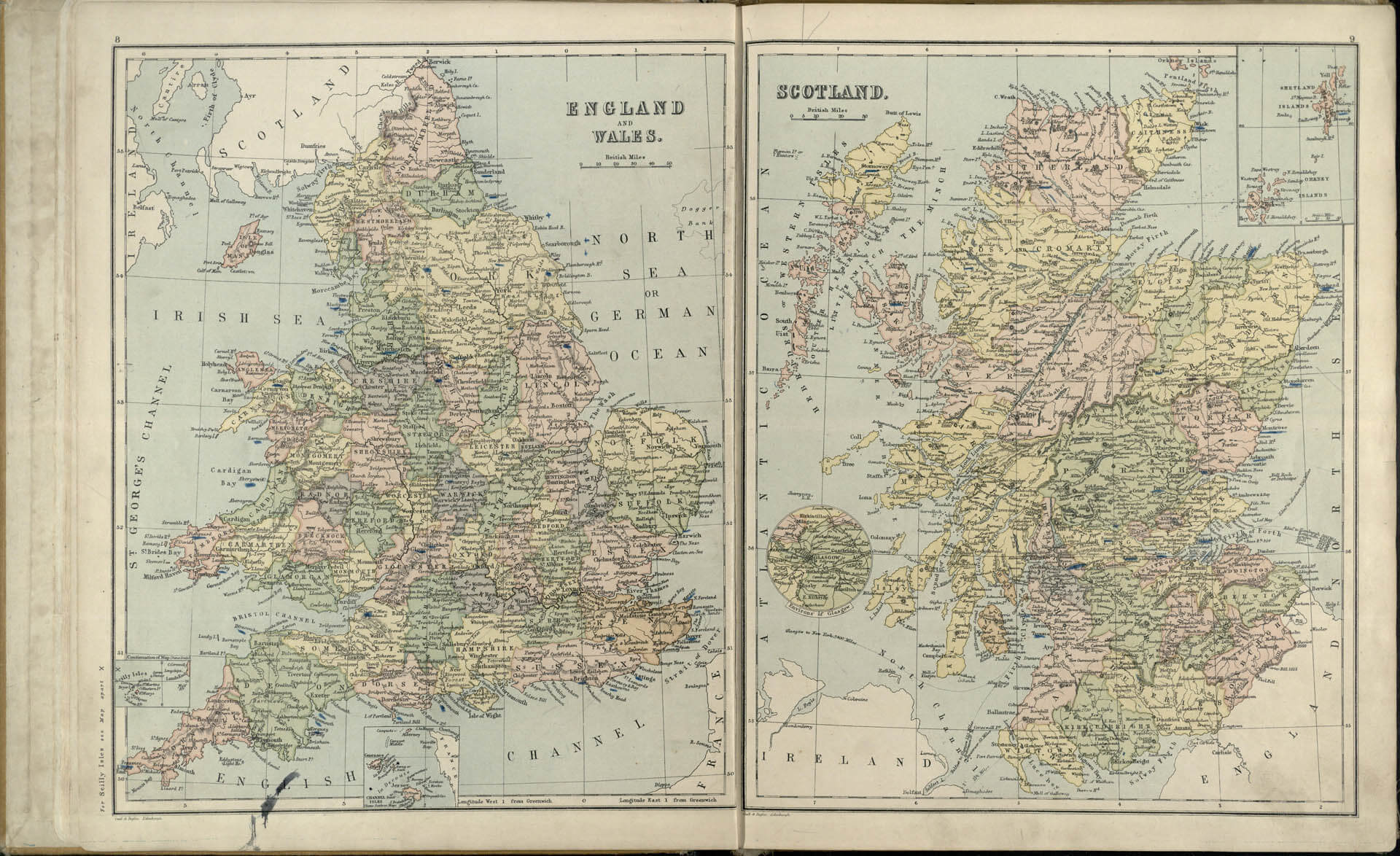

England and Scotland (Plates 8 & 9) each show more blue crayon marks than any other pages of the Atlas

Bibliography

Introduction

When I first realised how interesting and important the marks on the Sandycove Atlas might be for Joycean studies, I imagined that Joyceans would be eager to study it and assess its importance for themselves. It hasn’t happened like that.

I wrote a paper about the discovery and my initial view that it showed strong connections with Ulysses in particular. Gert Lernout and Dirk Van Hulle of the University of Antwerp were kind enough to carry it on the 2020 edition of their ‘Genetic Joyce Studies’ website as a ‘Nota Bene’ addition, where it still sits.1

However, there was little response from the Joycean community and my attempts to engage with individuals were met with polite blanking. It seemed that nobody wanted to consider the evidence. I came to realise that I would have to make the case myself, despite my lack of academic qualifications. (I have a Physics degree from Imperial College.)

I am not complaining. The decision to research the Atlas in more depth has led to some of the most exciting moments of my life. Discovering new joins between the marks in the Atlas, the text of Ulysses, the life of James Joyce and the findings of Joycean scholarship has proved richly rewarding.

A bibliography of the main works I have consulted to reach this point follows below.

Bibiliography

Ellmann, Richard, James Joyce: New and Revised Edition, OUP, 1983

Ellmann, Richard Ed., Letters of James Joyce, 2 vols, Viking, 1966

Erdman, David V, The Complete Poetry and Prose of William Blake, Anchor Books, 1988

Ferrer, Daniel, Genetic Joyce, Manuscripts and the Dynamics of Creation, University Press of Florida, 2023

Gorman, Herbert S, James Joyce his first forty years, Geoffrey Bles London, 1922?

Gorman, Herbert, James Joyce a definitive biography, John Lane The Bodley Head, 1941

Groden, Michael, Ed., Ulysses . . . a facsimile of page proofs for episodes 1-6, Garland, 1978

Gunn, Ian, and Hart, Clive, James Joyce’s Dublin: a topograhical guide to the Dublin of Ulysses, Thames and Hudson, 2004

Johnson, Jeri Ed., Ulysses: The 1922 text, OUP, 1993

Killeen, Terence, Ulysses Unbound: a Reader’s Companion to James Joyce’s Ulysses, Penguin Books, 2022

Maddox, Brenda, Nora The Real Life of Molly Bloom, Houghton Mifflin, 1988

Moro, Andrea, Joyce’s Ulysses Concordance, https://joyceconcordance.andreamoro.net/, accessed from 10 April 2020

Norris, David, and Flint, Carl, Joyce for Beginners, Totem Books, 1994; later as Introducing Joyce, Icon Books, 2000

Price, Stanley, James Joyce and Italo Svevo: The Story of a Friendship, Somerville Press, 2016

Whelan, Kevin, ‘The Memories of “The Dead”’, The Yale Journal of Criticism, volume 15, number 1, pp59-97, 2002